Hengistbury Head Geology

The approach to Hengistbury Head starts approximately 5 metres above sea level, this being just west of the Iron Age defences known as the Double Dykes . About 100 metres East of the Double Dykes the promontory rises steeply and starts to level off at about 30 metres. The head is 36 metres high at its highest point which is approximately a quarter of the way along or about 700 metres from its most easterly point. From this high point Hengistbury Head gently slopes down to a height of approximately 15 metres at its Eastern end. This gently sloping small plateau is known as Warren Hill. Approximately half way along Warren Hill, the Northern aspect of the Hengistbury Head is bisected by a nineteenth century open cast iron ore mine.

The approach to Warren Hill

As you walk along the beach below Warren Hill, one of the most memorable and distinct features of Hengistbury Head is the clearly defined Strata. The bottom strata dates back about 60 million years. The change in the strata over time illustrate the changing conditions and climate associated with this place. It should be remembered that Hengistbury Head, even with a base 60 million years old is still quite new. No dinosaurs ever walked here, as they had died out many millions of years before the first sands for Hengistbury Head were laid down.

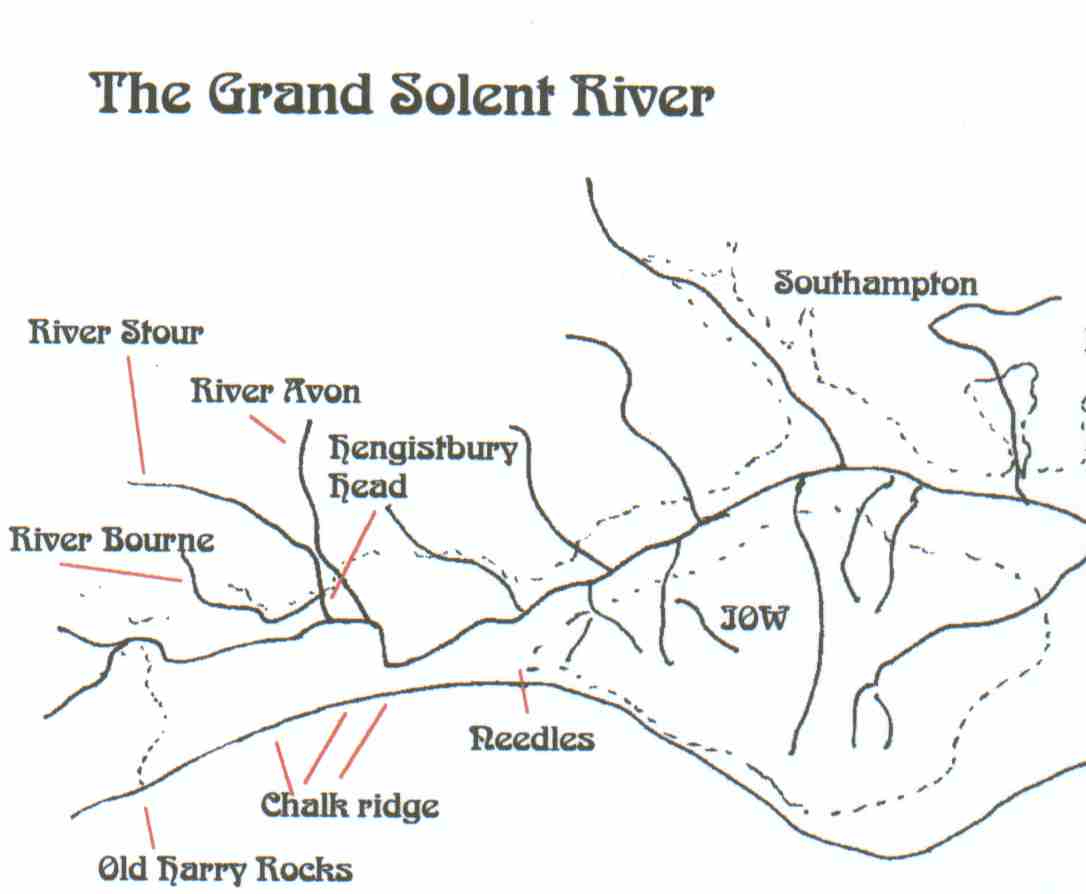

During the last Ice age (about 12,000 years ago) Hengistbury Head was several Kilometres inland. At that time the River Stour flowed to the South of Hengistbury Head while the River Avon flowed out to the North. Both of these rivers probably joined into the ancient River Solent that is believed to have meandered through what is now the area of sea between the Isle Of Wight and the mainland, known as the Solent. The Solent River originally flowed into the sea east of Southampton and was contained on its journey by a southerly chalk ridge stretching from the Needles at the Eastern end of the Isle of Wight to Old Harry Rock at Studland. Over time the river eroded into the chalk ridge as at the same time the sea cut into the ridge from the South. Eventually the ridge was breached. The river changed course and initially flowed out to the sea somewhere between the Needles and Old Harry Rock. Further erosion took place and over time the whole ridge was destroyed and the river valley was invaded by the sea.

Hengistbury Head cliff face showing strata

The River Avon and the River Stour originally took different routes to The River Solent. However eventually they eroded the land separating them and merged into one, near where Christchurch Quay is today. They then followed the path originally taken by the River Avon. The final stretch of the river bed originally used by the River Stour was abandoned.

After the Rivers Stour and Avon merged they followed the same course North of Hengistbury Head. Later on, another small river began to flow in the old Stour bed, but in the opposite direction. It is possible that this river was actually the small River Bourne. Although today this river flows out to sea several kilometres West of Hengistbury Head, in the past, before coastal erosion, the river hooked round and joined the Stour and Avon at Hengistbury Head.

The base of Hengistbury Head is formed from Boscombe Sands (a compressed and soft rocklike sand that is easily friable (crumbles)). Above the Boscombe sands is about 3 metres of greenish sandy clay known as the Lower Hengistbury Head Beds. This is topped with up to 15 metres of brown sandy clay. Embedded within this layer are large ( approximately 1-2 metres diameter) boulders of Ironstone. This is known as the Upper Hengistbury Beds. On top of this is about 3 metres of white compressed sand containing islands of clay. This layer is known as the Highcliffe beds. A layer of river bed gravel sits on top of this and is about 1 metre thick. Finally the top of the promontory is covered by a thin topsoil which in the main consists of windblown sand. All of the strata are inclined at about 3 degrees to the horizontal (declining to the south east).

Barnbight on a misty day. All the material here was laid down relatively recently and comes from the rivers

An imaginary view of what the Solent river may have looked like

The base of Hengistbury Head is formed from Boscombe Sands (a compressed and soft rocklike sand that is easily friable (crumbles)). Above the Boscombe sands is about 3 metres of greenish sandy clay known as the Lower Hengistbury Head Beds. This is topped with up to 15 metres of brown sandy clay. Embedded within this layer are large ( approximately 1-2 metres diameter) boulders of Ironstone. This is known as the Upper Hengistbury Beds. On top of this is about 3 metres of white compressed sand containing islands of clay. This layer is known as the Highcliffe beds. A layer of river bed gravel sits on top of this and is about 1 metre thick. Finally the top of the promontory is covered by a thin topsoil which in the main consists of windblown sand. All of the strata are inclined at about 3 degrees to the horizontal (declining to the south east).

Boscombe Sands

The Base of Hengistbury Head is built on a base of compressed yellow sand interspersed with layers of shingle. The overall colour of this soft rock varies from a whitish grey through to a mauve-brown colour. This colour variation is governed by the amount of organic material present in the rock and also on the moisture content. The sand grains making up the Boscombe Sands are generally rounded or sub angular grains of quartz. This type of formation is typical of material deposited on a sea beach. The shingle beds in the lower parts of this layer consist of well rolled flints which show signs of being battered by wave action. These flints are usually white or grey. The sandstone is devoid of large animal fossils because, being laid down on a shallow tidal beach or sand bank, there was no possibility of the animal remains being entombed in the sand and forming fossils. Some of the pitted flints contain small amounts of chalky deposits and they probably came from erosion of the nearby chalk ridge. The upper layers of the bed contains layers of bleached pebbles which were probably washed down from the surrounding hills to a shallow estuary.

Boscombe Sands (the bottom stratum) is clearly visible here

The lower levels of the Boscombe Sands contain minute fossils of the burrows of small crustations. Occasionally fossils of leaves and other vegetable material have been found but due to the friable nature of the Boscombe sands they are difficult if not impossible to extract.

The upper levels of the Boscombe Sands indicate that the previous sea beach environment was suffering under continuous flooding and submergence and the tidal and wave action effects which give the lower parts of this strata its disordered structure were becoming less dominant. Instead, without the massive influence of wave and tide the last few centimetres of this strata take on a more ordered structure with a finer grained sediment.

The Boscombe sands were created during the Eocene time period after the creation of the chalk ridge from Old Harry rock to the needles (Mesozoic time scale). The creation of the Boscombe Sands date back to between 40 to 60 million years. It is interesting to speculate that, as this was essentially a prehistoric beach, that the layers of flints were probably laid down by wave action, possibly during storms or other catastrophic events. While the composition and age of these materials is unimaginably vast we can still see unique short term events in their structure like the flint layers.

The Boscombe Sands are the lowest strata of Hengistbury head and due to the dip of 3 degrees eastward the stratum disappears below the level of the beach about half way along Hengistbury Head.

Lower Hengistbury Beds

The top of the Boscombe Sands is separated from the Lower Hengistbury Beds by a layer of black flints. This flint layer would indicate a sea invasion that signaled a sea level rise for at least part of the time period during which the Lower Hengistbury Beds were laid down. The deposits of this new strata are a maximum of 4 metres in thickness and are mainly glauconitic sandy clay. (Glauconite is a mineral with a greenish/olive colouring)

Another view of the strata. Notice the Iron Doggers on the beach and embedded in parallel lines in the Upper Hengistbury Beds

The type of formation indicates that it was formed as part of river estuary or delta with surrounding bogs, marches and swamps. The presence of Glauconite would also back this up. Glauconite is formed from an interaction of fine clumped clay particle with salt water. A river estuary would provide the ideal environment for this reaction to take place between in flowing sea water and the debris brought down to the estuary by the river.

This stratum is littered with the fossilised remains of prehistoric tropical and subtropical plants and ferns and occasional lignitic layers can be found as well. Lignite is a woody textured mineral derived from vegetation and is a bit a like a half way house between peat and coal. It can be burnt and is often used as fuel, although the deposits at the head are not extensive enough to have provided later human habitants with a fuel source.

The Hengistbury Head Beds used to extend to Alum Bay in the Isle of Wight which has similar structures to that found on Hengistbury Head. Elsewhere the Hengistbury Head Beds can be found in the bottom strata of the cliffs off Highcliffe and also in nearby St Catherine's Point.

The Strata at the easterly end. See the 3 layers of Ironstone Doggers embedded in the Upper Hengistbury Beds

Upper Hengistbury Beds

The Upper Hengistbury Beds are the most prominent of the stratum. They are approximately 15 metres thick and are a creamy brown colour. The most striking feature of this layer is the existence within it of large ironstone concretions, known as ironstone doggers. These vary in size but are usually at least 1 metre across with some being 2 metres. The Ironstones lie in almost parallel lines, there being between 3 and 5 layers along the cliff edge. These Ironstone doggers have been the main defence against erosion for the last several thousand years. The normal slow erosion that had taken place had caused the Ironstones to form a natural reef off shore. The boulders had also lined the beach protecting the base of the promontory. Their removal in the 1690's and the 1850's has been the main cause of the terrible erosion problems found at Hengistbury Head since then.

The Ironstone boulders were formed in a stagnant bog environment. Iron compounds were washed down by the river and formed a layer on the bed of an estuary. As the sea level fell the layer of iron compounds congregated into clumps and chemical reaction with a reducing agent (possibly Carbon from decayed vegetation) left the iron nodules we have today. The layering took place on many occasions and some of the doggers have layers like an onion. Within these layers have been found fossilised sharks teeth, vertebrae and unidentified vegetable matter. These concretions or Doggers were probably shifted from their point of creation to their locations with the Upper Hengistbury beds by flooding and storm. Below the bottom layer of doggers the Hengistbury Beds show signs of fossilised worm and crustacean burrows similar to those found in the Boscombe Sands.

The top cream coloured stratum are the Highcliffe Beds. Note the IronStones, before 1850 the whole beach would have been similarly paved

The Upper Hengistbury Beds also appear east of Hengistbury head in the lower stratum of the cliffs at Highcliffe. However there appear to be no Doggers in this area. A similar structure can be found at St Catherine's point, about 3 kilometres inland fro Hengistbury Head. Here the stratum is only a metre or two from the top of the promontory. I understand that some ironstones have been found embedded in it.

Highcliffe beds

The Highcliffe Beds mark the top layer of the Eocene stratum on Hengistbury head. Like the Boscombe Sands this layer appears to have been laid down on a sea beach and has a similar structure to that of the Boscombe Sands. Small areas of clay can be found in this layer. These are from the river erosion of clay patches that were previously the base of small lagoons or ponds. The clumps of clay were washed and rolled down by a river and ended up being washed up onto the beach by wave action. The clay lumps then became incorporated into the general make up of the stratum.

This layer also shows the typical sea beach feature of having bands of pebbles, each band probably indicating a large storm or short sudden incident. The Highcliffe Beds get their name for their more prominent location in the cliffs at Highcliffe, where they form the mid band between the Hengistbury beds and the Barton Sands.

Twenty years ago, on the beach near the Double Dykes, a large clay slab lay under the river gravel and in the Boscombe sands. These clay slabs are usually evidence of ponds and lagoons, but here this clay slab probably formed the base of the pond at some later date and was originally higher up in the strata, probably within the Highcliffe beds. It probably ended up where it is due to erosion of the area in which it lay. Like the Iron Stone Doggers it ended up being dumped on the beach while everything around it was washed away.

The Clay Slab on the Beach in 1999

The Upper Layers (Gravel and Top Soil)

Due to the proximity of the nearby river systems a great deal of river deposits exist on and around Hengistbury Head. These river deposits consist mainly of river gravel's and are some of the newest of the deposits at Hengistbury Head.

During the last million years a succession of ice ages have been interspersed by warmer sub Mediterranean style weather. During the cold periods large quantities of water became locked up in ice and consequently the sea level dropped. Due to the lowering sea level, rivers flowing into the sea had to cut down into their beds to reach the new lower level, this left their former river gravel's suspended above the new river bed in a terrace. The new river course flooded during the warmer periods when the ice melted and raised the sea level. The process repeated when the next ice age started. Depending on the duration and the severity of the cold periods the grading (cutting down) of the valley floor varied. The net result is a series of river terraces in a river valley. Three such terraces exist on Hengistbury Head and there is also the newer river gravel's from the former River Stour channel and the existing river system.

Just West of the Double Dykes is the former bed of the River Stour. After the River Avon and Stour eroded their dividing ridge and joined in a confluence about 1 kilometre north west of the Hengistbury Head the old Stour bed, which used to route the river to the south of Hengistbury Head was initially abandoned and then adopted by the river Bourne.

The gravel rich bed of the old Stour/Bourne river system where it ends on the beach west of the Double Dykes

Today the river Bourne flows through the middle of Bournemouth and enters the sea is a south-easterly direction. During the last ice age, when the area now occupied by Poole bay was dry tundra, the river Bourne probably continued further south and then hooked round and flowed into the confluence of the rivers Avon and Stour from a north easterly direction

The abandoned river bed west of the Double Dykes is probably the product of two rivers, each flowing in the opposite direction to the other. This river bed shows the typical formations expected from a river bed. The bed consists of sub-angular flints mixed in with coarse sand. The texture is similar to that of builders concrete aggregate before mixing in the cement. The whole mass is a sandy orange in colour. These river deposits, mainly from the Stour and Bourne date back about 10,000 years or less

The River Terraces.

The three river terraces on Hengistbury Head have been named after similar structures found near London although there is no direct correlation with the London terraces.

The Boyne River Terrace.

The oldest river deposits on Hengistbury Head are on the top of Warren Hill. These gravel's are known as the Boyne Hill Terrace gravel's. This layer of gravel's is probably of the order of 200,000 years old.

The Lower Taplow Terrace

The set of gravel's known as the Lower Taplow terrace converges with the Boyne Terrace at Warren Hill but mainly occupies the eastern side of Warren Hill.

The Second Lower Taplow Terrace

The newest set of gravel's that actually sit on hengistbury Head are the Second Lower Taplow terrace. These sit about half way down the head on the northern escarpment. These gravel's have been disturbed and covered by the spoil from the old open cast mine from the Hengistbury Mining Company. This area is now known as The Batters.

Topsoil

The majority of the topsoil on Hengistbury Head is made up from windblown sand and soil. It has a depth of about one metre although some areas around the Double Dykes, the depth is up to three metres.

The other major new deposits exist at the lower levels and are the recent deposits from the river Stour and Avon. The areas building up from these deposits surround Barn Bight, the Saltings and the northern coastline of Hengistbury Head.

New River and Beach Deposits

While Hengistbury Head has suffered massive erosion in recent times, there has also been deposition of materials on both the south easterly beach and the northerly harbour shore line.

The deposits on the northerly shore line of Hengistbury Head are traditional river deposits leading to the building of salt marshes and reed beds. These are most prominent to the west of the Double Dykes where they form an area known as the Wickhams. Further East, in front of the quarry there has also been a similar building of new land. These areas are locally known as the Salt Hurns and Rushy Piece. An interesting (though unrelated) item in this area is a deeper area of the harbour just off the Salt Hurns called Lob's Hole. Lob's Hole is caused by a fresh water spring that breaks out into the harbour bottom and is only visible as a spring at very low tides.

Barnbight seen from the Batters. The land surrounding this inlet has been deposited in the last thousand years

The breakwater has caused the rebuilding of the beach at the easterly end of Hengistbury Head

The building of the beach off the south-easterly aspect of the Hengistbury Head has been deliberately caused by the building of a set of groynes. The purpose of these groynes is to reverse the damage done by the removal of the Ironstones in the mid nineteenth century. The main build up of material has been to the West of the major breakwater built at the easterly extremity of the head in 1938.

Here there has been a major deposit of sand and shingle from long shore drift and the beach now probably extends out to close to its position in the late 19th century. The beach close in to the head has turned into a sand dune structure with grasses growing and further stabilising the immediate area. The growing sand dunes in the new beach area at the eastern end of Hengistbury Head testify to the success of the new beach defences